“Just the facts, Ma’am.” - Joe Friday

Let me tell you a story. “Wait,” you might say. “I thought this was a work of nonfiction!” It is. But see, all nonfiction is a story. That may be counter-intuitive at first hearing. We tend to think of nonfiction as the truth, or as what actually happened. In other words, we think of nonfiction as “just the facts.”

However, if you look at any of the books in the nonfiction section of a bookstore or library, you won’t find “just the facts” about anything. You’ll find writing that reflects the dictionary definition of nonfiction: “narrative prose offering opinions or conjectures upon facts and reality.” Delving further, we find that the word ‘narrative’ refers to “story or account of events whether true or fictitious.”

What this boils down to is that all nonfiction is interpretation. Nonfiction is interpretation of the facts from a particular point of view, with the biases and assumptions built into that viewpoint.

Interpretation includes opinion and conjecture, as well as explanation; it explains the meaning of things. The oldest part of our human brain is programmed to do that continuously, interpreting everything we perceive in terms of whether we need a response, be it fight, flight or freeze, or more generally, sensing whether what we are perceiving is of value in terms of survival. And it does this whether we want it to or not. It’s automatic.

Now, the brain needs a basis on which to interpret perception, and that basis is memory. Memory can be thought of as the recording of interpretation. We can look at our memories as a series of multi-sensory images (visual, audible, and so on) of what we have perceived. Those images tell a story, a story in pictures. Any time you’re thinking about things, you’re telling yourself stories. These stories explain what you have experienced and what you are likely to experience going forward.

What about when you’re not looking at your memories, but instead when you’re in the present moment experiencing something right now? In that case, you’re processing the information from your senses, and a larger part of your brain is figuring out what that information means. It’s interpreting what you see and hear with a much larger scope than fight or flight but built on that same structure. It’s telling you a story about what you’re perceiving.

I used to study physics.

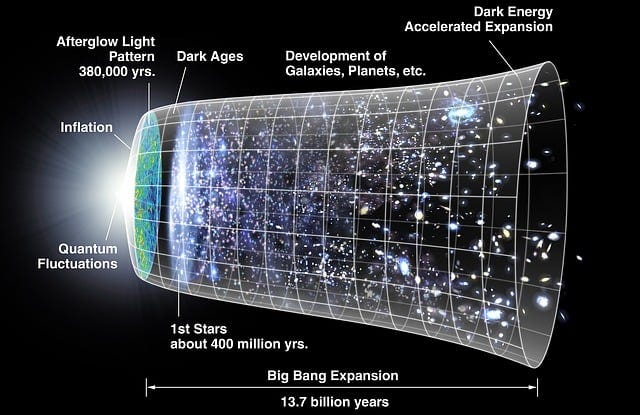

When someone asks me what part of physics I liked most, I tell them “cosmology.” Strictly speaking, cosmology is the science of the nature, origin and development of the physical universe, and it’s pretty obvious that a book about cosmology would be in the nonfiction section of the bookstore or library. But as we saw, nonfiction is a story, and cosmology is no exception. It’s an interpretation of the answers we’ve gotten as we ask questions like “How did the universe begin?” and “What determined how it came to be the way we observe it to be?” and “What happened before the big bang?”

We can also say that cosmology is an explanation. We human beings have explanations for everything. That seems to be part of what it is to be human. It seems that we have a basic hunger for them, for answers, for meanings. I am offering a specific explanation in this work, and it is the one about who we really are and what the world out there really is. It’s my preferred cosmology, so to speak, and it is an alternative cosmology to the one we inherited from our birth culture.

The story I’m telling you in this work is a story about searching for a deeper understanding of what it is to be a human being than the one we carry around with us. It is an account of an inquiry into that understanding based on the only raw material upon which such a search could possibly be based, and for me that is my own life experience.

Before I present this alternative cosmology, however, I will first summarize the one all of us already use, the story we tell ourselves. That way, we can distinguish one story from another. The story we have learned to tell about who we are and what the world consists of is represented by the water in our fish parable. You’ll find that parable in the previous episode. As I suggested then, we live inside our stories, and they’re transparent and invisible to us. But even so, we will see if we can get an understanding of them anyway.

How do we think about ourselves?

The metaphorical water we humans swim in consists of many stories with a common thread and a common basis, and the fact that they are stories, as opposed to facts, is rarely noticed. What is embedded in all these stories is the assumption that there is a world, it existed before you and I were around to experience it, and it continues to exist independently of us. In fact, in these stories the world has existed for a length of time measured in billions of years. Once it began, it continued to evolve according to the laws of physics, some of which we have managed to explain to ourselves and others we’ve not.

Let’s continue to flesh out this story. After an incredibly long period of time, life appeared on at least one planet, the one we consider the Home Planet. Creatures slowly evolved with the mental and sensory apparatus required to see, hear, feel, taste, and smell the world. And finally, after eons, humans appeared, creatures able to experience the world and in possession of the cognitive abilities required to think about it, to plan, to analyze, and even to understand.

According to the universally accepted explanation—what I call “the water” we swim in—what we humans are is first and foremost an enormously complex collection of atoms, atoms that form molecules, molecules that form cells, cells that form tissues, and so on. This progression of collections proceeds according to strict rules, rules which allow for variations and new forms. And somehow, according to this explanation, out of that enormous complexity arose awareness, thoughts, feelings, and emotions, all the strange and wonderful aspects to being human.

That’s the default cosmology, the story we inherited from our culture about our presence in the world. That story is rarely questioned; instead, it forms the basis of all our interpretations. For us, it’s simply the way it is. However, what if the idea that the world is the backdrop to our lives is an illusion? What if the permanence of the physical universe turned out to be simply part of the interpretation all of us make when we perceive the world?

See, I’m arguing for the consideration of a different cosmology. This other explanation, this other story we could tell ourselves, is a completely different story about what we are and why we are here. In general, I call it the “seer’s explanation.” By the way, when I use the word seer here, I’m not referring to seeing auras or energy fields or the future. I’m using it in the sense in which one suddenly recognizes the presence of something that previously had been invisible or just disregarded, as in the phrase “Ah! I see!”

This seer’s explanation is a description of human experience which is in sharp contrast to the ordinary explanation. It takes into account the transparency of the “water” we swim in and how that cognitive environment affects our lives, and it explains how we got to be swimming in that water. It takes into account the lessons of 20th century science, including the so-called “observer effect.” And it suggests how the recognition that all of our ideas about who we are and what’s possible for us lead to the possibility of living as the free beings we like to think we are.

Next time: Towards a New Cosmology

I guess it's time to go back and reread the Seer's Explanation again! It has been a while since I last read it!